Overview

In July 1845, Henry David Thoreau walked into the woods with a borrowed axe and a stubborn idea that if he simplified his life to the bone, he might hear what a human life is actually saying.

On the edge of Walden Pond, a mile or so from Concord, he built a one-room cabin, planted a bean field, and made a pact with quiet. The days were shaped by small, exacting rituals—cutting wood, brewing coffee, copying passages into his journal, watching the light move across the water like a slow admonition to pay attention. In that pared-down space, he wasn’t trying to escape the world so much as tune himself to it.

The picture we inherit is “hermit in the wilderness,” but Thoreau’s solitude was more art than exile. He walked to town, did laundry, argued philosophy, hosted visitors. He listened for the train whistle slicing the evening and for loons calling across the pond—reminders that civilization and wildness were neighbors, not enemies. His experiment wasn’t isolation as an absolute; it was a rhythm: retreat to clarify, return to test. He wanted to see which desires survived silence and which dissolved when the day had no audience.

Walden; or, Life in the Woods, was published in 1854. It grew from those seasons and reads like field notes for an inner life. Thoreau inventories beans and boards with the same seriousness he gives to conscience, as if to say: count carefully—your attention, your money, your hours—because what you measure you learn to respect. He mocks busyness and debt not from snobbery but from a craftsman’s concern: how can a person carve a self if their hands are always borrowed? The pond becomes his mirror; the cabin, a kiln. He enters lean and comes out tempered.

What makes Walden an ideal doorway for our topic is precisely this: Thoreau shows that solitude can be chosen, purposeful, and tethered. He wasn’t anti-social; he was pro-clarity. His “going to the woods” is less a geography than a method—reduce noise until meaning appears, then carry that meaning back to the village. In Indian context, one might say he discovered a touch of vānaprastha within a gṛhastha life; in Jung’s, he gave psyche a container so the Self could speak.

Lets start there—at the little cabin among pines, with a man learning to hear again. Not because we all need to flee to a pond, but because each of us needs a place (and a practice) where attention stops scattering and begins to hold. Thoreau’s gift isn’t a map to the wilderness; it’s a recipe for crafted solitude: simple, steady, porous to the world—so that when we step back into our lives, our presence has weight.

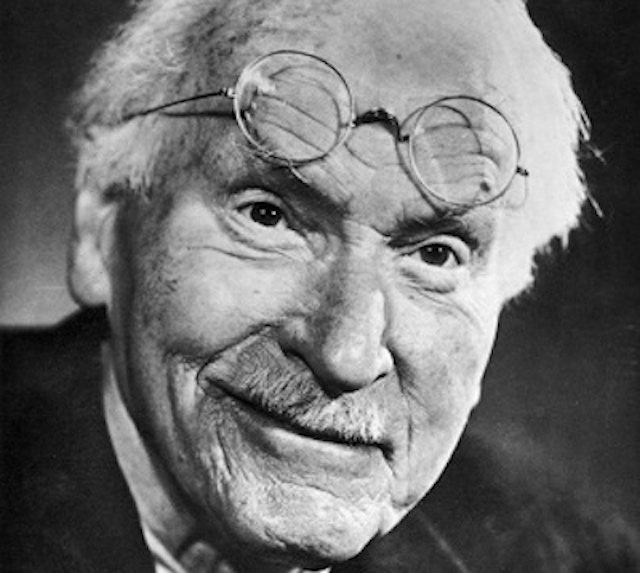

Carl Jung, half a world away, discovered a parallel truth. After his break with Freud, he entered a long “confrontation with the unconscious,” built his stone tower at Bollingen, and spent years cultivating a solitude that wasn’t misanthropy but method. For Jung, the psyche needs silence the way a lake needs stillness to reflect the sky. The point of withdrawal was not to disappear into private reverie; it was to individuate—to become who you are in truth—and then return to the village with gifts.

Imagine the Bhagvad Gītā as a quiet set of instructions whispered at daybreak. It does not romanticize caves; it simply says: find a clean, simple place and take your seat—not too high, not too low—with a steady body and gentled senses; then turn the mind toward its own source (Gītā 6.10–6.12, 5.27–5.28, 6.18). This is how the Gītā speaks of solitude: not a mood, a setup—a way of arranging place, posture, and attention so the self can become a friend to itself (Gītā 6.5–6).

It warns against extremes. Solitude is not starvation or excess; it is measure: neither overeating nor undereating, neither constant wakefulness nor constant sleep—moderation is the ground on which quiet stands (Gītā 6.16–6.17). In that measured stillness, the mind—“restless and unsteady”—is handled without drama: whenever it wanders, bring it back again and again to the inner seat (Gītā 6.26, cf. 6.34).

The Bhagvad Gītā’s instruction to sit in a clean, quiet place (6.10–6.12) is at once spiritual and neurobiological: reliable cues reduce arousal; an uncluttered field reduces distraction; a steady seat trains the body to trust stillness.

The text calls this “abiding in the Self alone,” an inner solitude you can carry anywhere; the “city of nine gates” (the body) becomes a place of ease when actions are laid down inwardly (Gītā 6.18, 5.13). Speech softens into mauna—a mental silence of clarity and restraint (Gītā 17.16). The qualities of knowledge include a liking for secluded places and a light touch with crowds (Gītā 13.10). As solitude matures, its signs are plain: evenness in joy and sorrow, a mind that neither lunges nor recoils, and a presence that harms none (Gītā 2.55–2.57, 12.13–12.15).

Near the end, the Gītā names the contemplative by simple marks: fond of solitude, modest in taking, restrained in body, speech, and mind (Gītā 18.52). None of this cancels action. The quiet it prescribes is not an exit but a clearing: sit apart so you can rise to your work without clinging, do what must be done, and keep the heart unharmed in the midst of men (Gītā 3.19). In the Gītā’s cadence, solitude is the workshop where peace is forged, and the proof of that peace is how one returns to the world—calm, clean-handed, and free (Gītā 6.15).

This essay brings the Indian rhythm and Jungian depth together with psychology and philosophy to draw a clean line between aloneness and loneliness, to show when isolation harms and when it heals, and to offer a practice for turning one into the other.

Aloneness vs. Loneliness

Aloneness, or solitude, is chosen, meaningful, rhythmic. It regulates the body, opens attention, and enlarges imagination. In Hindu terms, it cultivates vairāgya (dispassion) and viveka (discernment), pruning clinging so insight can grow.

Loneliness is unchosen disconnection. It tightens thought loops, elevates stress chemistry, and thins the sense of self. In Sanskrit you might call its felt tone tāpa (burning distress) and moha (bewilderment).

The difference isn’t semantic; the nervous system can feel it. In aloneness, the breath lengthens and the Default Mode Network (the brain’s introspective hum) settles into reflective spaciousness. In loneliness, vigilance rises, rumination spins, and the body subtly prepares for threat. The meaning we give to being alone—chosen practice or unchosen exile—changes its biology.

Hindu Pedagogy: The Forest as a Teacher

Vānaprastha, literally meaning ‘way of the forest’ or ‘forest road’, is the third stage in the ‘Chaturasrama system of Hinduism. It represents the third of the four ashramas (stages) of human life, the other three being Brahmacharya (bachelor student, 1st stage), Grihastha (married householder, 2nd stage) and Sannyasa (renunciation ascetic, 4th stage).[2]

Vānaprastha starts when a person hands over household responsibilities to the next generation, takes an advisory role, and gradually withdraws from the world. This stage typically follows Grihastha (householder), but a man or woman may choose to skip householder stage, and enter Vānaprastha directly after Brahmacharya (student) stage, as a prelude to Sannyasa (ascetic) and spiritual pursuits.

After the duties of student (brahmacarya) and householder (gṛhastha) are largely fulfilled, one begins a deliberate withdrawal from roles, possessions, and social display to cultivate inner clarity. It is not escapism but a transitional vocation: handing responsibility to the next generation, simplifying one’s life, and converting experience into wisdom through study (svādhyāya), discipline (tapas), and service (sevā).

These stages are marked by alone-ness. Such aloneness isn’t an eccentric preference; it’s a stage of life and a method of knowing. The āśrama system formalizes what many cultures only intuit: we need seasons of withdrawal to ripen understanding. Vānaprastha (forest-dweller) and sannyāsa (renunciation) are not escapes from responsibility; they are the disciplines that prevent responsibility from consuming the soul. In the Gītā, the aspirant practices “vivikta-deśa-sevitvam”—a fondness for quiet places (13.10)—not to hate the world but to see it clearly and re-enter it with steadier hands.

Vānaprastha is a pedagogy. Classically Vanaprastha meant retiring to a hermitage or āśrama. Modern day forest can be literal or a consecrated corner at home, but it always carries a curriculum: attend, simplify, inquire. It can mean creating a “forest” within ordinary life—downsizing, fixed hours of meditation and scripture, mentoring the young, periodic retreats, and a gentler public footprint. The essence is a shift from achievement to meaning, from accumulation to discernment (viveka), preparing the ground for full renunciation.

Sannyāsa (renunciation) is the fourth and final āśrama, the consecration of life to spiritual realization through renunciation. Here one relinquishes identity built on family name, career, and status, adopting the marks of a renunciate (externally or inwardly) and resting one’s sense of self in the imperishable. While Vānaprastha loosens the knots of attachment, sannyāsa cuts them, making liberation (mokṣa) the sole priority.

Renunciation in sannyāsa is not nihilism; it is a disciplined freedom from clinging. It requires isolation and silence as medicines for the mind’s restlessness: solitude to steady attention, silence (mauna) to refine speech into truth, and austerity (tapas) to cleanse habit. This seclusion is purposeful—awakening compassion and equanimity—so that the renunciate, whether in a cave or a city, lives as a quiet lamp: unattached, available, and inwardly free.

Sannyāsa intensifies that curriculum that began with Vanaprashtha. Roles and identities are loosened; adhyātma-vidyā (knowledge of the inner self) becomes primary. Śaṅkara, in Vivekacūḍāmaṇi, insists that discrimination ripens in minds disentangled from the crowding of objects. Yet even here, the rhythm remains: retreat and return. Hinduism rarely absolutizes solitude; it alternates it with saṅga (wise company) and sevā (service), so insight doesn’t calcify into forced isolation.

Jung’s Silence: Individuation Requires Solitude

In the western arena, Carl Gustav Jung’s lifelong question—how does a person become whole?—required silence.

Jung was Fraud’s beloved heir apparent until his theories conflicted with Fraud’s. When Jung broke with Freud in around 1913, he didn’t just switch theories; he lost a friendship, a professional home, and a worldview. He described the aftermath as a “confrontation with the unconscious.” By that he meant: instead of keeping busy to outrun the inner noise, he stopped—and let the inner world surge up. Dreams became vivid, day-visions arrived unbidden, moods swelled and receded like weather. He called this period “perilous” because it felt like standing on a cliff edge: if he clung to control, something essential would be missed; if he surrendered indiscriminately, he risked being swept away. The task was to stay related to the flood without drowning.

Out of that crucible he shaped a method he later named active imagination. Imagine sitting with a troubling image from a dream—a red snake, a dark hallway, a child at a window—and, instead of interpreting it immediately, you enter it. You speak to the snake: “What do you want?” You follow the hallway, even if it twists somewhere uncomfortable. You ask the child what she sees. You let the image answer back in words, feelings, sketches, gestures. Then you respond. It becomes a dialogue—ego and unconscious meeting on a small, protected stage. The point is not fantasy for its own sake; it’s to let autonomous inner figures present their meanings so that previously split-off parts of you can rejoin the whole. This is where Bollingen was born.

Bollingen is the lakeside hamlet on Lake Zürich where Carl Gustav Jung built his stone tower-house starting in 1923. He expanded it in stages over the next decades as a private retreat and workshop—no phone or electricity at first—where he wrote, carved symbols into stone, painted, and practiced the silence that fed his ideas (active imagination, individuation). Think of it as Jung’s “inner life made architectural”: a simple, symbolic place to contain and mature his psyche. Think of Bollingen as psyche made visible in stone. He carved inscriptions, arranged rooms with symbolic intent, and worked with his hands—masonry, carving, fire, water. Why stone? Because stone contains. It is slow, heavy, resistant—the opposite of a racing mind. By placing symbols into rock and arranging space with care, Jung gave the indistinct inner life a container: a real place where the intangible could settle, ferment, and take shape. This is what he meant by giving psyche a vessel. Without a vessel, volatile material either evaporates (you forget the insight) or explodes (it overwhelms you). With a vessel, it cooks.

That’s the metaphor behind his line “the tower wasn’t a lighthouse; it was a kiln.” A lighthouse shines outward to guide others. A kiln concentrates heat inward to fire clay. Bollingen wasn’t built to broadcast a message or create a movement. It was built to temper Jung—like clay hardened into durable pottery. He was not polishing a public persona there; he was firing the self: shaping, drying, heating, cooling—over and over—until what was soft and collapsible could stand on its own.

Linking this to his psychology, Jung saw personality as a living system with several key players: the persona (our social mask), the shadow (traits we disown), the anima/animus (inner contraries, feeling/relational vs. thinking/structuring poles), and the Self (a larger organizing center that includes conscious and unconscious).

After the break with Freud, Jung’s persona had cracked. Shadow material—grandiosity, fear, rage, tenderness—poured in. The inner contraries demanded attention. Active imagination gave these figures voices; Bollingen gave them walls. Between the voices and the walls, something new organized itself: not a bigger ego, but a more centered one, aligned with the Self rather than with any one role.

Notice the craft ethic in all of this. Jung didn’t just think about symbols; he worked them: drew them in the Red Book, carved them into stone, arranged them in space. He trusted that psyche speaks in image and form, not just in abstract ideas, and that working with matter grounds meaning. The hand helps the heart integrate. If you’ve ever felt that writing something by hand or building something simple in wood steadies you, you’ve tasted the same medicine.

And the “perilous” part? Jung warned that courting the unconscious without an anchor can inflate you (“I’ve discovered cosmic truths!”) or depress you (“I’m nothing but chaos”). The safeguards he used are the same ones he prescribed: relationship (he kept seeing patients and family; he didn’t disappear), symbolic discipline (he recorded, painted, carved—he didn’t just ruminate), and ethical testing (insights had to show fruit in conduct: clearer speech, steadier compassion, more truthful choices). If a revelation made him less humane, it failed the test.

So, in one sweep: after Freud, Jung turned toward the inner storm; he learned to dialogue with its figures (active imagination); he built a place where what he found could be held and worked (Bollingen); and he used that heat not to signal the world, but to fire himself into a more integrated vessel. That is why, for Jung, becoming whole required silence—not as withdrawal for its own sake, but as the medium in which the scattered parts of a person can hear each other, join, and endure.

Key Jungian ideas that refract solitude:

Persona & Shadow: Solitude loosens the persona (social mask) and makes shadow material visible without immediate social penalty. This is risky: what emerges can be grandiose or despairing. Without practice and ethical ballast, solitude can tip into inflation (“I am beyond ordinary people”) or into collapse (“I am nothing”).

Anima/Animus & the Inner Other: In quiet, we meet inner contraries—the parts we project onto partners and enemies. Developing a relationship with this inner other reduces the compulsions that isolate us in outer life.

Self vs. Ego: Individuation is the slow gravitation of the ego toward the Self, the organizing center of the psyche that is larger than conscious identity. The ego can’t make that turn in constant noise. Silence is the medium in which the compass reorients.

Return: Jung was explicit: withdrawal that doesn’t return to relatedness is not individuation but evasion. The test of the tower is the marketplace. Hinduism would recognize this, for solitude is sādhana (practice), and the proof of sādhana is karuṇā (compassion) and steadiness in the world.

Wiring, Guṇas, and the Social Thermostat

Think of human behavior as having two vocabularies that talk about the same thing. Modern psychology divides people into introverts and extroverts based on how social exchange charges or drains your battery, dopamine thresholds ie how much stimulation you need to feel engaged, and stress reactivity or how fast your body flips into stress and how long it stays there.

Hindu psychology talks about the guṇas—three tones of mind: sattva (clear, calm, bright), rajas (restless, driven, go-go-go), and tamas (heavy, slow, sleepy).

These are different languages, same goal: these explain why some days you want a crowded party and other days you want headphones and a window seat.

Your “social thermostat” is set by three layers. First is temperament (nature): the built-in settings you were born with—some people arrive chattier or calmer. Second is saṃskāras (imprints): experiences that trained your nervous system; if friends felt safe growing up, crowds may feel safe now, but if you faced chaos or bullying, big groups might feel threatening. Third is practice (nurture): the habits you repeat; like lifting shapes muscle, daily routines shape mood and attention.

Each guna has a helpful side and a risky side. A sāttvic tilt enjoys routines, a bit of silence, and thoughtful conversations—great for focus, but it can become rigid if overdone. Rājasic energy loves movement, projects, and people—great for getting things done, but it can turn into anxiety or irritability without rest. Tāmasic energy can ground you—think deep sleep and recovery—but can also sink into procrastination and numb scrolling if it isn’t balanced. You actually need all three: start with rajas, concentrate with sattva, recover with tamas.

None of this is destiny; it’s a first draft you can edit. If you feel too rajasic (wired and restless), add sattva: a morning walk, slower breathing, single-tasking, fewer notifications. If you’re stuck in tamas (slump), spark gentle rajas: sunlight, a 10-minute tidy-up, a short workout, a quick call to a friend. If sattva is low (foggy or chaotic), reduce noise: fewer tabs, clearer to-do lists, simple meals, consistent sleep.

Solitude on purpose—even 15–30 minutes most days—means no phone, just breathing, journaling, or reading something nourishing. It builds sattva (clarity) so you can hear yourself think.

Community on purpose—one or two “good-company” anchors a week like a club, class, faith group, sport, or volunteering—keeps you connected so quiet time doesn’t harden into loneliness.

That’s also the point of the Indian āśrama idea (life stages): whoever you are, you’ll need some solitude to grow up on the inside, and some community to keep that solitude healthy. At twenty, that can be as basic as a small daily quiet ritual plus regular, high-quality time with people who lift you. Get the rhythm right—inhale (go inward), exhale (show up for others)—and your temperament starts working for you, not against you.

A Chorus on Solitude: East and West

Across centuries and across continents sages converge:

Upaniṣadic voices push attention inward: “Through the mind alone is Brahman to be realized” (MU 3.2.4).

Patañjali pairs abhyāsa (steady practice) with vairāgya (dispassion): both flower in ordered quiet.

Ramana Maharshi insisted that true solitude is inner; you can carry a crowd into a cave or find the cave in a crowded train.

Gandhi braided āśramic discipline with public action, using silence and fasting as moral instruments.

Pascal: humanity’s troubles arise from our inability to sit quietly alone—an early diagnosis of the nervous flight from self.

Thoreau: solitude as companionship, “the companionable self,” anticipating modern findings on replenishing attention.

Nietzsche: solitude as the alpine air where new values crystallize—dangerous if it never descends, generative when it does.

Rilke: love as “two solitudes that protect and border and greet each other”—solitude as the condition of mature relation.

Hannah Arendt: thinking requires “two-in-one” dialogue with oneself; totalitarianism destroys solitude to prevent thought.

These are different vocabularies, one structure. Solitude is not the opposite of society; it is the root system of a life that can meet society honestly.

When Isolation Harms—and How to Transmute It

Isolation can fall into two categories. Alone-ness vs. Loneliness.

The best way to illustrate this is thru my own experiences. I spend most of my time in a tiny village of Whangaroa. It has 100 inhabitants, no commercial activity, and my contact with other human beings is limited to maybe once every few months. The place, and my existence here, invigorates me, I feel spacious, I have choices, and though I can return to civilization anytime I want, the aloneness is healing, nurturing. I avoid all conflict and suffering that comes from being in a metropolitan. Life moves slowly, days are longer, there is ample time to do much. I can concentrate on my reading, writing, and contemplate on deeper aspects of life, which would be greatly difficult, if not impossible, in other parts of the world. The stillness, and the silence has immense growth potential. “I don’t need anyone,” “I am enough,” “I grow in and thru silence.”. This voluntary solitude (aloneness) is chosen, meaningful, rhythmic. It rests the nervous system, deepens attention, and enlarges imagination. In Sanskrit you’d call its fruits sattva (clarity) and viveka (discernment).

But this same place, this beautiful little village, would constrict many, the lack of commercial activities would stifle them, and lack of human contact would create a sense of loneliness. For most, a prolonged stay here would constitute forced isolation or unwanted solitude. This unwanted solitude constitutes loneliness, an unchosen disconnection. In Sanskrit, its tone is tāpa (burning distress) and moha (bewilderment). It tightens thought loops and can elevate stress load if it’s felt as exile. This loneliness corrodes. Physiologically it amplifies inflammation, depresses mood, and dulls cognition. Psychologically it breeds self-referential loops: “No one needs me” becomes “I don’t matter,” and perception reorganizes to confirm the script.

Love and the Two Solitudes

Imagine that our hypothetical woman, Meera is married to Arun—ordinary people with jobs, bills, and a WhatsApp family group that never sleeps. This is gṛhastha life, the householder stage: cooking, caregiving, showing up for each other. For years they did what couples do—shared logistics and, without noticing, also shared unfinished inner work.

When Meera felt anxious, she wanted Arun to be endlessly soothing. When Arun felt unseen, he wanted Meera to admire him on cue. Both were asking the other to carry parts of themselves they hadn’t developed yet.

One winter, Meera began waking early. No big vow—just twenty minutes before sunrise, sitting quietly with tea and a notebook. Arun, who thought silence was “not his thing,” started taking a slow evening walk without headphones. Nothing changed on Instagram, but something shifted inside.

In terms of Indian culture, each created a small “forest,” a vānaprastha-like pocket in gṛhastha life. The marriage didn’t disappear when they went to their forest; it deepened. That’s the first point: householder life isn’t annulled by solitude; it’s refined by it.

Here’s how. The Bhagvad Gītā talks about svadharma—your own dharma. Meera’s early-hour quiet showed her that beneath the anxiety was an old pattern: she left her needs unspoken, then resented Arun for not intuiting them. Her svadharma wasn’t to make Arun more psychic; it was to learn to name her needs simply. Arun’s walks revealed something too: the admiration he craved from Meera was really a piece of his unlived self—a creative side he had shelved to be practical. His svadharma wasn’t to wring applause from Meera; it was to give that side of himself a home (he began sketching at night). Each started doing their own inner task instead of outsourcing it to the other.

Meera was protecting Arun’s evening walk—she didn’t guilt him for it—and Arun protecting Meera’s dawn time—he kept the kitchen quiet. They were not walking away from each other; they were walking toward themselves, and then returning. The result was less friction, not more, because they stopped treating the relationship as a repair shop for inner shortages.

Jung helps explain the mechanics. He said we often project our anima/animus—our inner “other” (the receptive/feeling side in men, the assertive/discerning side in women, loosely speaking)—onto partners. Meera had projected her assertive voice onto Arun: she wanted him to speak for her. In solitude she practiced saying one clean sentence about what she needed, no drama. Arun had projected his feeling/creative life onto Meera: he wanted her warmth to substitute for his own neglected warmth toward himself. On his walks he began meeting that inner other directly—by sketching, by feeling small griefs he’d parked for years.

As they reclaimed these projected parts, intimacy changed flavor. Before, a Friday night might spiral: Meera hinted, Arun missed the hint, resentment rose, both felt abandoned. After a few months, the scene looked different. Meera said, “I’d like us to eat together, just us, no phones.” Clear, kind, no test. Arun, who’d already honored his sketch time earlier in the week, could meet her ask without feeling erased. That is encounter – not entanglement. Encounter is when two people meet as people. Entanglement is when two incomplete selves trying to use the other to finish unfinished business.

Notice what didn’t happen: they didn’t move to a cave, they didn’t become “less married,” and they didn’t stop helping each other. They simply stopped demanding the impossible: “Make me whole in the places I won’t visit in myself.” Solitude—those small, steady pockets—gave them tools. Meera grew a voice; Arun grew warmth toward his own creative life. When they came back to the shared table, they brought those gains with them.

Thus, gṛhastha life (married life) is not annulled by the forest; it is deepened by it. Your shared life gets richer when each person has a private workshop where they do their svadharma.

Rilke wrote: “love consists in this, that two solitudes protect and touch and greet each other.” He’s pointing to differentiation, not detachment: two people who each have a solid inner life, and who meet from that fullness. “Solitude” here means you’ve done enough of your own inner work that you don’t need the other person to plug your leaks or carry your unfinished business. You can choose closeness instead of clinging to it.

Think of it like two gardens with a shared gate. Each garden is tended—weeded, watered, alive on its own. The gate is open often; you stroll back and forth, share cuttings, plan seasons together. That open gate (warmth, affection, help) is the “touch and greet.” The fence (boundaries, self-respect, private time) is the“protect.” Without the fence, you get overgrowth and resentment; without the open gate, you get cold distance. “Two solitudes” is the balance: boundaries that guard each person’s becoming, and a welcome that lets love breathe.

In practice it looks warm, not chilly:

You each keep a small solitude ritual (walk, meditation, studio time) and the other protects it. You make clean asks (“Can we have dinner together, no phones?”) instead of hints or tests. You don’t demand the other supply what you refuse to grow in yourself (Jung’s point about projections). After time apart, you return with something to share—insight, patience, art—so the relationship is nourished by your solitude.

So “two solitudes” isn’t living apart; it’s loving with presence + boundaries. Rilke’s “two solitudes” isn’t cold distance; it’s respectful space that lets love breathe. And Jung’s warning is practical: if you keep asking your partner to carry your unlived parts, the relationship buckles. If you spend a little time meeting those parts yourself, the relationship becomes lighter, kinder, and more honest.

The Paradox That Frees

Aristotle quipped that one who needs no society is beast or god. Hinduism answers more gently: you are a becoming—and becoming requires rhythm. Jung agrees: the self takes shape at the edge between inner and outer. So we alternate—like breath—world and forest, conversation and silence, action and contemplation. We practice until aloneness becomes a skill and loneliness a teacher.

And when we return from the “forest”—whether from an hour’s vigil, a season at the hermitage, or a meditation course conducted in silence—we carry what both traditions prize: a quieter gaze, steadier hands, and a self big enough to serve. The village is the same; the one who returns to it is not the same.

Conclusion

In the end, the question isn’t “alone or together?” but “with what rhythm—and to what end?” The digital age floods us with contact while starving us of communion; it offers noise where we need musical notes. Indian wisdom answers with form. Jung adds the craft of guarding thresholds. Rilke’s line—“two solitudes that protect and touch and greet each other”—names the social fruit of this inner work.

Together they restore the very capacity modern life erodes: steady attention. With attention intact, quiet becomes solitude instead of isolation, and company becomes communion instead of chatter.

So let the conclusion be simple and old-fashioned: alternate like breath. Go inward to remember, outward to give. Treat attention as sacred fuel. Keep a little forest in your day and a little village in your heart. In that cadence, “isolation” becomes a skill.

Like, Subscribe and leave a Reply