I recently happened to have an interesting discussion on Lacan with an acquaintance. The discussion has inspired this weblog. Although there are many, many, many posts that I have written on Lacan in the past, I am pulling out all the plugs once again, drenching myself in the psychology of desire, one of my most favorite from the psychoanalytic treasure-box.

Given the complexity of Lacanian thought, and the scarcity of people who read Lacan, I have a feeling that this post may well be one of the least read posts in the history of this blog, but what can I say – I submit to the creative forces that permeate my existence. Consider this an attempt to re-structure my own thoughts and feelings about Lacan. in this new life stage – the sunset of my life.

If you happen to be here, do read the blogpost in full. Concept in the second half are very meaningful for understanding our everyday desires and how they affect us.

There appears some duplication and redundancy in the post, even some omissions of key concepts. Please bear with me while I refine it – putting the article together has been a rigorous attempt, taking a few days – and nights.

Brief History Of Lacanian Thought

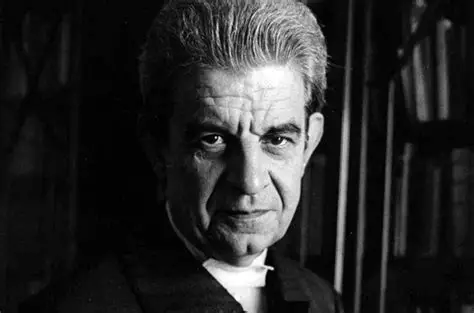

Jacques Marie Émile Lacan (1901–1981) was a French psychiatrist-psychoanalyst who created a trend “return to Freud” by reading Freud in context of linguistics, structural anthropology, and philosophy. Trained at Sainte-Anne Hospital in Paris, he first made his name with a 1932 thesis on paranoia (the “Aimée” case), circulated among Surrealists, and in 1936, he presented his well known paper on “mirror stage”. At around 6 – 18 months, a baby sees their reflection, and gets excited, and thinks, “That whole, coordinated person is me!” The mirror shows a single, tidy whole. So the child’s first sense of “I” (the ego) is “unified in appearance.” There is a happy “aha!” when he recognised himself in the mirror, a phenomenon Lacan called “jubilant identification”.

But inside, the baby still feels messy and uncoordinated—bits of body, waves of need, emotions all over the place. So right from the start there’s a gap between the smooth image that he sees in the mirror, and the lived, chaotic experience of his psyche. Lacan coined the phrase “internally divided” to represent this gap.

Lacan’s main point was that our ego is born by taking an outside image as ourselves which arises from a nearby parent saying “Look, that’s you!”. Because that image looks better than how the child feels inside, the child then spends a lifetime trying to live up to their parent’s image of him—chasing wholeness, approval, and control. That basic split (ideal image vs. felt self) is normal, but it fuels things like insecurity, rivalry, perfectionism, and our sensitivity to how others see us.

From the early 1950s until 1980 he taught an almost continuous series of weekly Seminars—public, often theatrical lessons that became the main vehicle for his theory. Alongside, he wrote a super-dense tome, the 1966 volume Écrits.

Lacan’s central claim is that the unconscious is “structured like a language.” He recast Freudian concepts via three interlocking hierarchical orders—the Imaginary (images and identifications), the Symbolic (language, law, kinship), and the Real (what resists symbolization).

When Lacan says “the unconscious is structured like a language,” he means our unconscious doesn’t just store raw urges as Freud posits. Lacan holds that the unconscious organizes and expresses these urges through signs and rules—much the way sentences do.

The unconscious also speaks in signifiers, using bits of language—words, sounds, images that stand for something. Because of this, dreams and slips of the tongue feel like puns, jokes, or cryptic messages.

If metaphor swaps one thing for another, metonymy moves sideways, letting meaning leak along neighbors. The unconscious often travels this path and in analysis we track these links. A detailed description of how metonymy expresses itself, is provided in the blog that I posted many years ago. Advertising exploits the chain by wrapping products in nearby signs of status and belonging. In analysis we track these links: the point isn’t the last item in the chain, but the thread of desire that keeps shifting along it.

The unconscious follows its own rules (not the grammar-class rules). Freud saw two main dream moves: condensation (many things packed into one image) and displacement (emotion moved onto something “safer”). Lacan maps these moves to language moves: metaphor that uses substitution, and metonymy that constitutes association/slide. The unconscious “writes” with these moves.

And the meaning that we ascribe to these written words comes from differences and links, ie words don’t carry meaning all by themselves. They get their meaning from how they differ from other words and how they link to other words around them.

Eg, in explaining the differences, Lacan would say that Bank (money) isn’t bank (river) until context separates them; cat isn’t cot because one letter differs. In Lacanian terms, a signifier is defined by what it is not—its neighbors keep its boundaries sharp.

In explaining links, Lacan holds that the context weaves meaning to the word. A word picks up sense from the chain it sits in: “key witness,” “key change,” “key of C.” The word “key” is the same, but it links to different networks and means different things in language. Lacanian theories are supported by the dictionaries where every definition provides more words—meanings built from connections to other signifiers.

An unconscious meaning shows up from how a word or image repeats, rhymes, or links across your stories, and addresses anOther. We’re born into other people’s words – and think of ourselves as a “good girl,” “difficult,” “gifted” etc. The unconscious forms inside that web of words, so our symptoms and dreams are messages—meant for an imagined listener – even if we are unaware of the fact that these are meant for the Other. And these messages, for the Other, leak into our speech and acts. Slips, jokes, “accidents,” recurring bodily tics, odd choices, and more specially, dreams—none of these is random according to Lacan. These are signs trying to say something you haven’t yet said directly. Direct expressions from the unconscious, tugging at the helm of the conscious world like a little child attempting to be heard.

Whatever disagreements Lacan, Jung and others that followed may have had with Freud, all agreed on one thing: what is left unsaid by the patient, becomes as important in therapy, as what is said.

Many of Lacan’s signature concept come from these beliefs : the Name-of-the-Father (a symbolic limit that makes desire speakable), objet petit a (the elusive object-cause of desire), the phallus as a signifier rather than an organ, and the solvable equation which holds that one’s “desire is the desire of the Other.” These are discussed in greater detail in the following section.

Clinically, Lacan is accredited with introducing variable-length sessions (“scansion”), and emphasizing the subject’s relation to speech and signifiers over ego strengthening.

Lacan broke with the International Psychoanalytical Association in 1963 over training standards. He then founded the École Freudienne de Paris in 1964, and abruptly dissolved it in 1980, after which many students regrouped in Lacanian schools. His seminars moved from Sainte-Anne to the École Normale Supérieure, drawing a generation of French thinkers and writers.

Lacan worked in the intellectual crosswinds of post-war Paris. He was in dialogue and/or rivalry with Claude Lévi-Strauss, a structural anthropologist, Roman Jakobson, in linguistics. Lacan drew on Hegel, and Heidegger, and he argued with Sartre and Merleau-Ponty. His teaching influenced stalwarts such as Louis Althusser, Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray, Jacques-Alain Miller, who was his editor as well as his son-in-law, and, internationally, thinkers like Slavoj Žižek and Judith Butler.

Sometimes embraced, other times resisted, Lacan’s reworking of Freud—through language, law, and desire—remains one of the 20th century’s most durable provocations in clinical theory, literary criticism, and cultural analysis. He is perhaps the only psychoanalyst who used mathematical notations to explain psychic complexity.

Brief Introduction To Lacan’s Legacy

We are not tabula rasa. We don’t come into the world as blank, quiet organisms who slowly collect needs. We arrive into language—into a web of names, rules, stories, and expectations that existed long before us. Jacques Lacan’s project is to show how this web that he labelled as the Symbolic, shapes our loves and losses, our symptoms and ambitions, and even the very way we ask for anything at all.

Two of his most provocative ideas are the “law of the father” and the claim that “man’s desire is the desire of the Other.” If the first says, “there is a limit,” the second says, “there is a witness.” Together they explain why desire is never just instinct, never just “I want x,” but is always knotted up with prohibition, recognition, and the gaze we can only hope to meet. Lacan refuses to reduce them to biology or patriarchy. They always show up in ordinary life, and they still matter in an age of notifications and public performance.

The Three Terrains: Imaginary, Symbolic, Real

Lacan divides psychic life into three interlinked orders:

The Imaginary: As explained in the previous section, the imaginary constitutes the image, identification, mirroring. In his “mirror stage,” the baby spots a tidy, coordinated image in a mirror or he looks at the caregiver’s face/voice and jubilantly identifies with that wholeness. The key move is : “Aha! That’s me! I am that image”

The price is a gap between how we feel inside –fragmented, needy–and the sleek image of wholeness that we each chase. The imaginary thus fills the realm of pictures and likenesses—how we see ourselves vs how we want to be seen. Inside, the baby, and by extension all of us, feel messy/fragmented, but on the outside the baby, and each one of us, chases the sleek picture of wholeness.

Eg, a toddler wobbles but points proudly at their mirror self—“me!” The image looks balanced; their body doesn’t feel that way yet. The teenager copies a friend’s look, a fashion trend, or a celebrity’s vibe to “be someone.” Most rivalries in the world are image related rivalries. Social media filters, branding, “aesthetic”—all curating a look to glue a shaky sense of self. And in relationships, “Couple goals” are based on envy where the couple compares their private mess with other people’s facebook reels.

The pitfall lies in treating images as the whole truth. Ergo: If I look perfect, I am okay. Such desires create a need for perfectionism, competition and rivalry.

The Symbolic: This constitutes the network of words, rules, roles, and kinship that existed before us and that which slots us in our role—as the mother/father/child, student/teacher, citizen/defendant; calendars, titles, procedures, grammar. The network of Names, the No! ’s—grammars and taboos—that give us a place, make us individuals in the wider spectrum of the social orders, and make meaning possible.

The most important part here is that one has a Name and that Name has limits. One is required to submit to those limits, to speak and negotiate within those limits. And it is within those limits that meaning arises, and becomes possible. Within those limits, desire becomes sayable – one can ask, wait, bargain.

Limitlessness would lead to disorder/psychosis.

The downside is that a person cannot be everything that they desire because the world says “not now,” “not that,” “not this way” or simply “this way.”

Eg: in a family, “First dinner, then dessert” is a small no that lets wanting be spoken and timed. In school or at work grades, deadlines, job titles place limits, and a person is forced to operate within those limits. In Courts, or in a bureaucratic situations, labels like “plaintiff,” “vexatious litigant,” “approved/denied” are signifiers that carry power beyond any photo. In cultural context taboos, etiquette, pronouns abound. Such rules of interaction let conversations and communities hang together.

A pitfall arises when rules ossify. That is when the Symbolic can feel like a cage – eg empty titles that are devoid of power and authority, weaponized procedures that are used to harm instead of regulate.

A more detailed description of the symbolic is beyond the scope of this blog, but one begins to see that the limits, or boundaries, create social order.

The Real is all that resists symbolization. It is not “reality” but the stubborn kernel that can’t be fully expressed, that which will not fit neatly into images or language.

Things like trauma’s rawness, bodily pain, traumatic shock, the scream that doesn’t translate into words. The unthought known, and the unknown thought. The thing that keeps returning in symptoms which bring our patients into therapy.

The most significant mover here is that it just doesn’t fit. It is raw, intrusive, sometimes absurd, and “returns” where we least want it.

Eg: a toothache, a panic attack, sudden grief—no caption can make it stop. In trauma, you try to tell it like it is, but you hit a wall, and cannot make anyone understand. The nightmares repeat instead. Then there are slips of tongues and symptoms where you meant to say one thing, another pops out. It is a compulsion that won’t listen to reason.

In the most critical moments of the crisis, everything seems perfect(Symbolic), the selfie is flawless (Imaginary), but your gut says “something’s wrong” (Real). The mistakes we make in such a situation, we trying to solve the Real with more polish (Imaginary) or more rules (Symbolic) alone.

How These Three Braid In Life

In learning to speak, a child moves from the Imaginary (“I am the picture I like”) into the Symbolic (he names the objects around him, he takes turns and patiently waits for his turn). When language fails, the Real – the mess inside of him – erupts as a tantrum.

In dating scenarios, the person moves from the Imaginary (profiles, chemistry), thru the Symbolic (boundaries, consent, timing). The Real shows up in a breakup as the ache he can’t cognitively tidy up.

In Courts and other administrative proceedings, the Symbolic frames (forms, titles) meet the Imaginary theater (how you’re seen by the authority figures). When a label erases your voice, the Real arrives as rage or despair that “won’t fit the form.”

In psychotherapy or in meditation, the patients bring their Imaginary stories from their life, which are their (flawed) perception of reality (“how I appear”). They learn Symbolic nuance by finding their words to express, and gradually touch the Real safely in that what was unsayable, unfeelable, unknown at the beginning of therapy/meditation, starts to be said/felt/expressed.

We live where the three overlap.

Unconscious Is Structured Like A Language

The expression The unconscious is structured like a language means your unconscious doesn’t just store raw urges; it organises and expresses them through signs and rules—much like sentences do. It speaks in signifiers (words, images, sounds that stand for something), and it uses language-like moves: metaphor (one thing substituted for another—Freud’s “condensation”) and metonymy (meaning sliding along associations—Freud’s “displacement”). That’s why dreams feel like riddles, jokes, and puns; why slips of the tongue say more than we meant.

Meaning emerges from differences (“bank” ≠ “riverbank”) and links (the chain around a word), so what returns in symptoms is not brute instinct but a message with a structure.

In practice: you plan to say “Nice to meet you,” but you have a slip of tongue and out comes “Nice to need you”—a neat metaphor that reveals a wish for recognition.

You dream of keys the night before a talk; all week you’ve said “key points,” “key takeaways,” “the key to this problem”—your unconscious is writing in metonymic chains.

Lacan’s point isn’t just pedantic; it’s purely ethical. If the unconscious is written, you can listen to your own writing. And by catching your recurring words, rhythms, and slips, you can identify your needs, and desires, and then choose to say directly what you were saying sideways, thru dreams, metaphors, and thru these slips of tongues.

The symptoms often loosen once what had to be acted out can finally be spoken.

The Law of the Father is a Function, not a Person

In Lacanese one meets the Name-of-the-Father (Nom-du-Père). Despite the thunderous phrase, it does not mean “your biological dad” or an endorsement of patriarchy. It names a function of the Symbolic: the arrival of a third term that breaks the dyad of infant and primary caregiver and says, in effect, “there is a rule, a schedule, a language, a world beyond the mother-child dyad.” It intervenes in the incestuous relationship, as the Other, creating a trinity.

Thus the Name of The Father, or the Law of the Father is a Symbolic function that interrupts the Imaginary bliss of merger (me–mother–milk are one and the same) and, paradoxically, makes desire and expression of that desire possible.

This is the most important and the first/primal law – the law of limits. It shows up in many guises—another parent, a grandmother, a teacher; the clock; the phone that must be answered; kinda like the fact that words have meanings that you didn’t invent. In mythic shorthand, Freud wrote it as “You shall not sleep with your mother,” the incest prohibition. Lacan differs from Freud in that he hears a structural message in that prohibition rather than a moral sermon than:

There is a No! — a limit — that opens a name (a place in language).

The pun matters. The No! of the father (non) is also the Name of the Father (nom): the child learns that desire must be spoken, negotiated, and deferred. He learns that one day in the future, he would have his counterpart who would love him almost like his mother does. A metonymy. And he learns to wait.

Hence, this “No!/Name Of the Father” cuts the overwhelming, potentially engulfing satisfaction of a perfect fusion with the mother.

It introduces a lack—an absence. And human beings spend a lifetime circling that absence. That lack is not a pathology. It is the robust engine of desire.

Without that limit, we are not free; we are flooded. With it, we can want, and we can address an Other who might answer to our needs, demands and desires.

Three Layers Of Asking : Need, Demand, Desire

Lacan dissects our asks into a heirarchical ladder:

- Need is biological – eg hunger, warmth.

- Demand is need routed through language and addressed to another: “Feed me,” and “love me.”

- Desire is what exceeds any particular satisfaction. Even after the body is fed, something remains—the wish to be wanted, to count, to be important for the Other.

Since desire is threaded through with the Other’s response, it never belongs to us the way hunger does.

Desire is never just “for the object,” it’s also for the Other’s wanting. Our wanting is always social. We don’t just want the thing (the job, the bag, the person); we also want the recognition wrapped around it—to be wanted by, or valued in the eyes of, an important Other who could be a partner, peers, a crowd, an internalized parent. That is why a toy becomes irresistible when another child reaches for it, or a so-so restaurant suddenly matters when “everyone” is lining up. We follow fashion, music, and other trends.

The object is a vehicle; the deeper charge is the Other’s desire—their gaze, approval, or envy—circling the object and making it glow. And this is why Lacan can say: desire is the desire of the Other.

Desire of the Desired: Wanting the Wanting

Think of a 7-year-old who’s lukewarm about reading. In class, the teacher’s face lights up when a child reads aloud; there’s a Friday ritual where the “reader of the week” shares a favorite passage, and classmates lean in. Reading isn’t just a task now—it’s wrapped in the teacher’s desire, her visible joy, and the group’s desire expressed through their eagerness, and their attention. The child starts practicing at home, not only to “get through a book,” but to win that glow of recognition—to become all that the Others are wanting him to become. Soon the books carry the charge of that wanting. The child volunteers to read, asks for more difficult stories, and keeps going even when it’s tough. It’s not a bribe; it’s desire learning to speak the language of the valued Other, and that social spark pulls real skill forward.

People paraphrase Lacan’s line—“man’s desire is the desire of the Other”—in a few converging ways. All of them help. We desire what we perceive the Other to desire. The toy becomes valuable when someone else reaches for it; the trend becomes hot because the crowd’s gaze heats it. We desire to be desired by the Other. We crave recognition: “See me. Choose me.”. And we desire to know what the Other wants from us. We ask Che vuoi?—“What do you want of me?”. This phrase haunts desire with the anxiety of interpretation.

The directionality of the desire is of special interest. Desire is a triangulated social emotion—me, object, Other. Even in solitude we stage an audience: a parent, a critic, a future reader, an algorithmic feed we imagine applauding. In isolation, was talk to ourself, invoking the third. Thus, desire is not reducible to consumer mimicry; it’s the deeper human orientation toward the gaze and ear that confer meaning.

Desire gives rise to envy, rivalry, and shame. The Others want the same magnetizes objects that we desire, so we compete for the place, the approval of the Other. The laws impose a limit – we cannot be everything to your our first love; there is their other, and the whole world in fact. If we have learnt to submit to limits, the limit then redirects that rivalry toward speech, play, creativity, and social inscription.

When the law is too rigid, desire freezes into compliance; when it is too absent, desire burns into compulsions. And as a psychotherapists, we see these rigidities, and absences reflected in the room, and in our interactions.

The Paternal Metaphor: Swapping Tyrannies For Signifiers

Modern psychoanalysis does not treat Fraud’s imagery and importance of the sexual symbolism as being literal. For example, Lacan rewrites Freud’s Oedipal drama as a metaphor, not as a family soap opera. What must enter the child’s world is not a patriarch’s fist, anger, confrontation as a divider, but simply a signifier that situates the mother’s desire. It asks What does the Mother want? under a larger rule of culture, language and the shared calendar of the world.

Lacan calls this the paternal metaphor. It substitutes the signifier of the phallus (not the organ phallus, but simply a marker for desire’s place in language) for the child’s fantasy of being the mother’s sole satisfaction.

This swap is painful for the child. It is a loss of imagined omnipotence for the child, which feels like castration in Lacan’s technical sense. But its payoff is freedom: you no longer must be everything for One; you can pursue something among many. You can write, study, flirt, build, create. It emphasises that the desire can circulate.

Eg: While parenting, a toddler reaches for a fragile vase. “No” isn’t mere repression; it sets a boundary that allows curiosity to survive without catastrophe. The child learns their wanting has a world to negotiate. Over time, rules create psychic rooms in which desire can meaningfully play. In romance, we don’t just want someone; we want to be wanted by someone whose wanting we esteem. Dating apps turbo-charge the Other’s desire—metrics and matches offer a public proxy for desirability. Anxiety spikes around che vuoi?—“What do you want from me?”—so we read and reread texts for clues. In work & recognition, a promotion means money, but it is also symbolic place—a new name, title, office. We crave the Other’s acknowledgment that our signifier carries weight.

In social media, the Desire is staged before an algorithmic Other. Likes model the Other’s desire, trends fasten desire to branded objects; outrage gives desire a hot negative object. The line between wanting and wanting-to-be-seen-wanting blurs.

And in creative life, we make to be read, heard, seen. The law—deadlines, formats, editors—feels like a constraint, but it’s also a frame that channels desire into art instead of endless daydreams and scribbles on paper.

Limits, then, are a necessary part of the parenting responsibility. According to Lacan, the first limit that is set, is the No! In the name of the Father. Enforcing the Law of The Father. This No! is enforced with great rigidity, and creates a neurobiological structure, which according to Lacan, shapes the unconscious.

If the paternal function fails in that there’s no credible Name/No!, two extremes threaten. Either the dyad remains fused and unlivable, leading to some variant of psychosis. Or, the subject seeks tyrannical substitutes—leaders, ideologies, addictions—to impose an artificial law. This behavior of an Anti Social personality is simply a defence mechanism, seeking learn the ways of No!, in the Name of the Father.

The function of father does not have to be the physical, biological or any man acting as a father. The function can be carried by any caregiver or institution. Often religion substitutes for the function. When the function is performed by an entity that serves the function of the primal father, itestablishes good enough limits, and gives the desire a psychic contour, reshaping the unconscious without crushing it. The psychic energy thus freed can be used to engage more holistically with the life, and the world.

Object a: The Little Lure That Keeps Desire Moving

Why doesn’t desire ever rest, one may ask. It never rests because signification never closes. Something escapes every naming. Think of meaning as a net you throw over experience. However fine the mesh, something always slips through. That “something” is what Lacan calls objet petit a—not the object you want, but the spark that makes any object feel charged. Because words get their sense from differences and links, and there is never a final, fixed meaning, signification never closes; there’s always a little remainder, a thought, a feeling, an emotion that cannot be fully expressed in words. And, so, desire keeps moving to chase that remainder. The objet petit a, the object-cause of desire, isn’t a thing so much as a lure: a voice, a look, a fragment of memory, a perfume, the curve of a phrase. We chase it through objects and people, but it’s really the gap we circle. Lacan explains it thru the term metonymy.

Eg: In romance, you don’t just want this person; you’re hooked by that laugh, that glance—an inimitable glint you keep trying to recapture. When you get closer, the glint slides elsewhere. In buying things, the phone is great, but what you really craved was the unboxing buzz, the promise of a fresh start. In the next model you follow the same chase. In creating art or in work, a writer pursues the curve of a sentence; a musician pursues the grain of a tone. Perfection is unattainable, no piece exhausts that gain, no piece is perfect, so the act of making continues. When confronting memories, and nostalgia, it’s not the beach itself, but the smell of sunscreen, of the salt, of a voice from childhood. You cannot bottle it, so you circle it through places and objects.

Advertisers exploit this by borrowing the Other’s gaze. They use influencers, five-star ratings etc, to make an object glimmer with the promise of that a. Lovers do it too: we endow a person with the glow of our lost thing. The ethical question is not How do I kill desire? but How do I own my desire without reducing the Other to a prop?

The task is to recognize that the objet a is a lure, not a prize. When you “get the thing,” the lure often shifts, which is why satisfaction fades and desire reattaches to another object which seems to promises a more intimate experience that the current or previous one. Ethically, the task isn’t to capture that essence, for you can’t possibly capture it, but to recognize your lure and give it a dignified circuit—create with it, play with it, let it animate love without turning people into props for your desire. In analysis, in meditation, or upon reflection, naming your particular a helps you desire with responsibility, sans any compulsion.

Common Misunderstandings & Feminist Concerns

The feminists like me are concerned that the law of the father is a patriarchal relic, but no fears. That is only possible if one mistakes the function for father. Lacan insists the paternal function is structural—any figure or institution can carry it. Healthy limits can be set by a mother, two mothers, a grandmother, a teacher, a community. The trouble isn’t “fathers” but unmediated fusion on one side and arbitrary tyranny on the other. The function’s task is to symbolize desire, not to dominate bodies.

But does the desire of the Other mean we’re sheep?Not really. It means desire is intersubjective. Recognition , wanting love — these are human traits. They are not weaknesses. The ethical turn is to become responsible for the Others we elect to stage—and to recognize how culture scripts what becomes and is allowed to be desirable. We are free to write, and re-write, our place in that script.

What about trauma and inequality? some ask. Lacan is structural, not sociological, but these differences do not create contradictions or enmities in their standpoints. Structural insights help us read how power moves through signifiers—labels that punish (“vexatious,” “hysterical”), ideals that exclude (“good mother,” “model minority”). Law, when weaponized, can become a dead Name of The Father that forecloses speech. The analytic aim is to re-open speech so the subject’s desire can be owned rather than crushed or acted out.

Psychotherapeutic Sessions As A Place To Speak Desire

So how is a Lacanian psychotherapist different from the rest?

Lacanians listen for signifiers. They not only pay attention to the “what happened?” narrative from the patient, but how the patient says it—the recurring words and metaphors that hook patients’ desire to the Other.

They respect the law that enables speech. The analytical frame – times, fees, boundaries – is not a bureaucratic nuisance. It is the basis of treatment, a paternal function that keeps the work from dissolving into reassuring chatter or intrusive fusion.

They aim at desire, not conformity. Lacan’s ethical slogan—often paraphrased as “do not give up on your desire”—doesn’t mean to indicate that we are free to chase any whim. It means that we are to discover the particular way in which our desire speaks, without collapsing it into the Other’s script or into self-destruction. Jung call the autonomy – with responsibility and accountability – as individuation.

As desire clarifies, symptoms loosen and the patient heals —because he is no longer secretly asking the Other to define him every time he acts. He can negotiate the law rather than either rebelling against it or clutching it like a shield.

Living With The Law & The Gaze

A mature stance is not to abolish either law or Other, but to de-absolutize them. Limits are necessary; they also evolve. Recognition is necessary; it’s not ultimate. We can learn to ask: Which Others am I staging? Which “laws” actually help my desire breathe? The answers shift across life phases—parenting, partnership, work, aging, illness, grief.

We can Name our No’s and our Names, and identify which boundaries actually let our desires play (sleep times, tech limits, work frames)? Which titles trap us (perfect parent, perfect son, flawless activist), and which titles free us (novice, learner, neighbor, and yes, in my case, h\the vexatious litigant)?

We must always track desire’s witnesses. When making a choice, whose imagined gaze are we addressing? An old teacher, an absent parent, a crowd? Sometimes simply noticing the audience loosens its grip, and we acquire the freedom to make our own choices.

We must locate our object a. What tiny lure animates us—a tone of voice, a gesture, a color, a problem-type? Instead of chasing it blindly through people or purchases, we can, and must, fold it into our craft. Build with it, write from it, love through it without reducing others to it.

Conclusion

Lacan can sound severe. And complex. In fact his books are generally read thru “Guides To Read Lacan”. And these guides have their own guides “How to Read Guide To read Lacan.” Which spells the complexity and profundity of his teachings. But then, what less can one expect? After all, he defends something precious: desire as a living, speaking force. He thinks the subject is born not in the warm bath of fulfillment in the mother-child dyad but at the cut—the moment we learn that we are not all, we are not all-important, that we must speak, wait, plead, play. The “law of the father” is that cut, the paradoxical gift of a limit that keeps love from swallowing us and making life insufferably, overwhelmingly psychotic. And the “desire of the desired” is the reminder that we cannot desire alone, that we are made and unmade in the eyes of those we address.

In a culture that oscillates between limitless consumption and punitive moralism, Lacan is oddly humane. He says: you need a law—one that speaks rather than punishes. And you need an Other—one you can choose, resist, replace, answer back to. If you can hold both—limit and witness—your desire will have a runway that will help you launch yourself, instead of a cliff that leads to psychic death. The rest is craft and courage. We learn to speak our desire, accept the losses that make it human, and consent to the laws that help the desire breathe. Then the old sentence reads like a responsibility – Since the desire is the desire of the Other, choose your Others and your laws wisely, and do not give up on your desire.

Like, Subscribe and leave a Reply