It was a moody, cloudy day. A day which left nothing to be done, except write. Besides, I was pretty accurate in assessing the readership of Lacan on my last post. Whereas there were significantly large number of readers on my website in general, only a total of 8 visitors read the blog on Lacan in over a week. Geez, that hurt! Not because my blog had gone unread, but because it reverberated the resistance offered to one of the most brilliant minds in psychology and philosophy. Well, I love his work so much that I intend to keep writing about him, regardless of the audience. And I empathise with the frustration and pain felt by the true Lacanians of the world. But what does that mean? Empathy? Empathising? Being an Empath?

Over a period of past few decades of professional interaction with my patients, I have been repeatedly told that I am an “empath,” and that most of the problems arising in my life are due to my inability to enforce boundaries necessary for such a personality trait. Perhaps people – supervisors, educators, friends, patients – are right. So what better way to process these traits through written words?

As defined in the Mirriam Webster dictionary, the word empath, pronounced as em·path is a noun, meaning “one who experiences the emotions of others : a person who has empathy for others.” The example the internet version of the dictionary gives is:

If you feel the Earth’s pain before an earthquake or have a panic attack because someone near you is anxious, you might be an empath too.—Hannah Ewens

Thus, in modern lexicon, the term empath takes on an almost-supernatural quality. An aura, an awe is associated with the word that describes a person who doesn’t just understand others’ emotions, but who absorbs them, feeling another’s joy, anxiety, or sorrow as if it were their own. Empaths are often taken to be spiritual beings, gifted with a rare and ethereal sensitivity that sets them apart from the ordinary folks like the rest.

From a psychological standpoint, many who identify as empaths are known to possess the trait of Sensory Processing Sensitivity. Their empathy is a function of a highly tuned, deep-processing nervous system that absorbs emotional data from the environment much more than the average person is capable of absorbing.

Neuroscience points to the mirror neuron system as a key player in empathy. For the empath, this internal mirroring might be so vivid that the line between ‘your feeling’ and ‘my feeling’ can temporarily blur, leading to that classic experience of taking on another’s emotional state.

Psychology distinguishes between understanding a feeling and sharing it. An empath excels in affective empathy—they don’t just understand another person’s joy or pain, they viscerally feel it alongside them, which turns to being a gift but it also makes them vulnerable.

In spiritual circles, an empath is often described as ‘energy sensitive’ or clairsentient. Like a sponge, they unconsciously absorbe the emotional energy of their environment. Their body and emotions become a reflection of the unseen ‘vibes‘ around them.

Some metaphysical frameworks, like the Indigo/Crystal Child concept, view empaths as forerunners of a new consciousness. Their sensitivity is reframed as a mission to absorb and transmute the dense energies of the planet through their own highly tuned being, paving the way for a more compassionate world to emerge from the old.

And, last, but not the least, the Wounded Healer archetype helps explain the origin of many empaths’ gifts. Often born from a need to navigate a complex or painful childhood, their sensitivity was a survival tool that matured into a profound capacity for healing connection.

But what would the pioneering psychologist Carl Jung, a man who mapped the depths of the human psyche with scientific rigor and symbolic wisdom, have said about this phenomenon? He never used the word “empath,” but his entire body of work provides a profound, nuanced, and ultimately more useful framework for understanding it. And I will concentrate on Jungian concepts in this weblog.

Jung never really talked about the term empath, so there is not much to directly fall back on. Whereas his scientific mind would have likely dismissed the notion of a “superpower,” he would see the empath not as a spiritually evolved being, but as a person operating in a specific, and often primitive, psychological state—a state with immense potential for both – the profound connection and the profound suffering. This suffering endured by an empath would make the journey of the Jungian empath not be about celebrating a gift of empathy, but about undertaking the heroic work of transforming a unconscious condition into a conscious skill.

His Analytical Psychology decidedly rests on and incorporates functions of transference, countertransference and projective identification, which are enhanced in an empath during a session.

The Core Concept: Blurred Boundaries and Participation Mystique

To understand Jung’s view, we must first abandon the idea of solid, impermeable selves that remains untouched in an encounter with the other – whether in social life, family life, or in psychotherapy. Jung introduced the concept of Participation Mystique (or “mystical participation“), a term he borrowed from anthropologist Lucien Lévy-Brühl. This term describes a primal, unconscious state in infancy where the infant is merged or fused with the mother, and cannot distinguish itself from the external object, the mother. This Participation Mystique is a permanent state of mind, and recurs in later stages of life, throughout the lifetime, which enables one to fuse with another person, a group, or even a totem.

For the empath, this is the master key. They are not simply sensitive; they are in a constant, unconscious state of participation mystique with the emotional fields of those around them. Their ego boundaries—the psychic membrane that defines where “I” ends and “you” begins—are porous, fluid, or underdeveloped. Not very healthy – eh?

Imagine walking into a room where someone is silently furious. When a person with well-defined boundaries enters the room, he may notice the tension, feel a sense of unease, and think, “He is angry.” The empath, in a state of participation mystique, doesn’t observe the anger from an objective viewpoint. They unconsciously merge with the anger.

In my case, I would identify with their reasons. I became their social activist. My heart rate would increase, my stomach would clench, and a wave of irritable fury would washe over me. I didnt feel for the person; I felt as the person. For a moment, however brief or extensive, I participated in the other’s inner reality so completely that it would become my own. It affected me exactly the way it affected the other. Sometimes even more profoundly, being a person with a very strong ethical and moral structure.

Instead of being a chosen act of compassion, my empathy was always an involuntary psychic enmeshment. Jung would argue this is less a gift and more a relic of an undifferentiated psyche, a throwback to a more primitive, primordial consciousness where the embryo, the infant, the individual, the mother, and/or the tribe were one. I existed in the undifferentiated participation mystique.

The Wounded Healer

The Wounded Healer archetype is based on the powerful idea that our deepest pains and struggles are not just wounds to be healed, but can become the very source of our unique ability to heal and guide others. A wounded healer is the one whose own pain becomes a source of insight and empathy. The idea traces to Chiron in Greek myth and to Jung, who noticed psychotherapists are often drawn to the work by their own wounds.

The wound is a personal experience of suffering, trauma, illness, or “otherness.” The healing is the long, conscious process of facing, integrating, and making meaning from that wound. The healer is the the person who, having transcended their own suffering, can now offer profound empathy, understanding, and a map for others who are lost in similar terrain.

The core principle is that one must be familiar with the darkness to effectively guide another through it. The wounds of the healer help because lived experience sharpens attunement—they can notice nuances, build trust faster, and can name what others feel but can’t say. The risk is that the unhealed material can leak. Over-identifying, rescuing, boundary slips, burnout, or turning the client into a stand-in for healer’s own story. The wound of the healer is not a disqualification; it is the qualification. It forges a compassion that cannot be learned from a textbook. The task before the healer then, is to turn wound around into work, ongoing personal therapy/supervision, clear boundaries, somatic regulation, and the humility to keep learning.

As someone has said, use the wound as a lamp, not a leash

The Psychological Engine: The Dominant Feeling Function

Jung’s model of psychological types provides the mechanics of how this enmeshment occurs. Jung identified four primary functions: Thinking, Feeling, Sensation, and Intuition. The empath is almost certainly an individual with a highly developed, and likely Extraverted Feeling (Fe) function.

Fe is the function concerned with harmony, relationship, and the objective values of the collective. It’s a radar constantly scanning the social and emotional environment, assessing the mood, evaluating what is acceptable, and seeking to create and maintain connection. A person with dominant Fe is naturally attuned to the needs and feelings of the group.

This Fe is the empath’s primary tool. Their psyche is oriented outward, toward the human environment, and their Feeling function is so acute that it picks up the subtlest shifts in emotional weather, also being the source of their apparent clairvoyance. Empaths are master readers of non-verbal cues—tone of voice, body language, the energy in a room—processing this data instantly and unconsciously through their feeling valuation.

However, their strength has its shadow. When this special function is unconscious and untamed, it leads to a loss of self. The empath’s own values, needs, and emotional truth become subordinate to the atmosphere they detect. They become a chameleon, changing colors to match their emotional surroundings, not out of deceit, but out of a psychic imperative for harmony. They don’t know what they feel; they only know what is felt around them. This is a draining way to live, leading to erosion of their identity, to burnout and a deep sense of emptiness.

The Deep Waters: The Collective Unconscious and Psychic Infection

The empath’s sensitivity can also extend further outwards, extending beyond the other. They can feel overwhelmed by the anguish of a stranger on the news channels. They can experience the collective anxiety of a society in crisis. Jung would explain this as the empath having a particularly porous connection to the Collective Unconscious.

I happened to catch the 7-11 bombings in live. I was a stock trader in California at the time, and arose at 5am PST, leaving the CNBC on. Even after the initial shock wore off, and others continued with their life, work, and responsibilities, I distinctly remember being sick, bedridden, exhausted, and unable to function for the entire day. My neighbor had to take care of the two babies – an infant and a toddler – in my care.

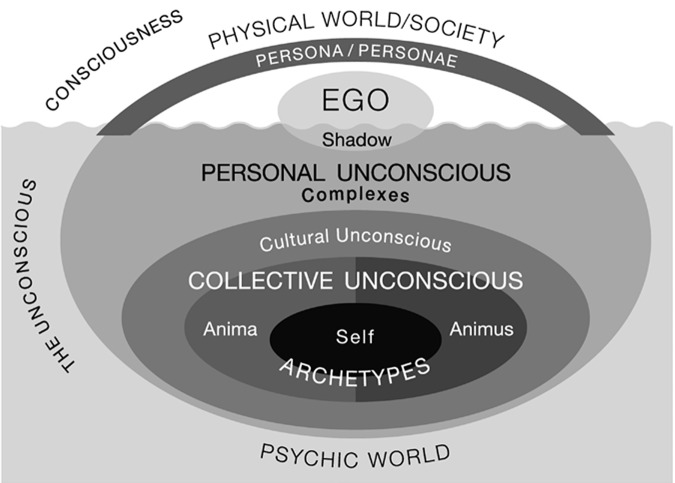

The Collective Unconscious is the deepest layer of the psyche, universal and impersonal, shared by all of humanity. It is the wellspring of our myths, dreams, and archetypes—the primordial patterns of human experience like the Mother, the Hero, the Trickster, and the Victim.

And for the empath, this is not an abstract concept; it is a daily reality. They are not just tuning into their colleague’s stress; they are tapping into the universal, archetypal experience of suffering or persecution. Perhaps my social activism, the absolute dedication to women’s rights can be put into context now. And since the empaths feel the sufferings registered in the collective, their reactions may seem disproportionate. I am not just feeling a single person’s emotion; I am often flooded by the raw, unrefined energy of an archetype. The anguish I feel about my own wounds, or the wounds of others, is amplified many times over.

Without a strong ego to act as a filter, these raw energies constitute psychic infections. And unfortunately, empaths like me mistakes these powerful, transpersonal energies for their own personal problems.

The weight of the world literally becomes our weight. We become a vessel for archetypal dramas, playing out the role of the savior who must fix everyone, or the victim who is crushed by the world’s pain.

This dark, concealed psychic cost is the “gift of empathy.”

The Individuation Journey: From Sponge to Mirror

So, are the empaths amongst us doomed to a life of being a spiritual sponge, perpetually waterlogged with the emotions of others? The answer is a resounding no.

I had to learn, through much suffering, that the trauma and suffering that I had endured, was the wonderful catalyst for a greatest journey: the process of Individuation.

Individuation is the lifelong process of becoming the unique, indivisible individual one is destined to be, integrating the conscious and unconscious parts of the psyche.

For the empath like me, this was the journey from being a sponge, to becoming a mirror in which the other, a group, or a tribe could witness their own problems. I learnt to separate “mine” from “thine.” It was a process, a journey of learning, involving time, effort and much patience.

Developing Conscious Discrimination: The “Mine vs. Thine” Practice

The first and most crucial step was to break the state of unconscious participation mystique. This requires brutal self-honesty and constant introspection. The empath must learn to pause in the face of a strong emotion and ask the simple, revolutionary question: “Is this mine, or does it belong to the other?” This question constitutes an act of psychic sovereignty. It creates a moment of space between the stimulus, and the identification with the stimulus.

Through practices like journaling and mindfulness, I began to trace the origins of my feelings. Did this anxiety arise after a phone call with someone? Did this lethargy descend when I walked into the office? Do I feel elevated, angry, depressed, happy etc, after a particular conversation with a particular person. Or conversely, what is the reason behind my happiness, anger, depression etc?

Such inquiries are not to build walls or to isolate oneself from others. Rather, they are acts of drawing a map, kinda like making an inventory list, a process of teaching oneself how to stand in the river of collective feelings, without being swept away by the current that does not belong to me.

Confronting the Shadow: Embracing the “Selfish” Self

Separating oneself from the other, from the tribe, from the environment may well feel, or be seen by others, as an act of selfishness and is the empath’s greatest fear.

It is seen as a Shadow element in the geography of personality. The Shadow, in Jungian terms, is the part of the personality that the conscious ego rejects. For the kindly, accommodating empath, the Shadow is a seething cauldron of seemingly “unacceptable” qualities: rage, selfishness, boundaries, judgment, and the capacity to say a firm, even cruel, “no.”

In order to survive in his prior life, the empath has often learned to repress these qualities with immense force. Society crushes rebellion, individuality, and rewards mediocrity, conformance and normalcy. Regardless – the repressed does not disappear when it is unacknowledged. It gains power in the dark. The journey to wholeness requires the empath to turn and face this Shadow. This process is called embracing the shadow. They must acknowledge, “I have a right to my anger. I have a right to put my needs first. I have a right to be separate.”

When I refuse to care what the world will think of me, I am truly free. I have embraced my shadow. I care enough for myself to own my warts, and the perfection.

As a Buddhist story goes, King Pasenadi of Kosala came to the Buddha, delighted and excited. He told the Buddha that his queen, Mallika, had said to him: “My lord, I love myself more than anything else in the world.” He had then asked her, “Well, do you love me more than yourself?” to which she replied, “No, my lord. I love myself more than you.” The king expected the Buddha to find this shocking or disappointing. Instead, the Buddha responded with deep wisdom. He agreed with her and then explained to the king:

Having traversed all quarters with the mind,

One finds none anywhere dearer than oneself.

Likewise, each person holds himself most dear;

Hence one who loves himself should not harm another.”

Instead of being an endorsement of selfishness or narcissism, the Buddha’s statement is a profound observation of a universal, psychological truth that forms the basis for all ethical conduct and genuine compassion.

Every living being instinctively seeks happiness and wishes to avoid suffering. This is the most basic, driving force of existence. Queen Mallika was simply being utterly honest about a truth that governs all beings. We are all, by our nature, oriented toward our own well-being. However, there is a critical twist. The Buddha uses this universal self-love not to justify selfishness, but as the very foundation for empathy and moral behavior. His logic is impeccable: Since I know how much I love myself and want to avoid suffering, and since I can see that every other being loves themselves just as much and wants to avoid suffering just as much, therefore, if I truly “love myself,” the most intelligent and consistent thing I can do is to refrain from harming others because harming others creates conflict, animosity, and negative karma, which ultimately circles back and causes me suffering. A world where everyone acts with consideration for others is a safer, happier world for me to live in.

The teaching doesn’t stop at “do no harm.” This is just the starting point for the development of Metta (Loving-Kindness) and Karuna (Compassion). Once you have established a feeling of kindness and care for yourself, you then extend it outwards: to a loved one, a neutral person, a difficult person, and finally to all beings without distinction. The message is: Your own well-being and the well-being of others are not separate.

The queen’s honest confession became the Buddha’s tool to show the king that the path to a harmonious kingdom and a happy life begins with understanding this interconnectedness. Hence, integrating the Jungian Shadow is not about becoming a monster; it is about gaining access to the vital energy and self-protective instincts needed for survival. It provides the backbone that the feeling function lacks. The empath with an integrated Shadow can feel your pain deeply, but can also say, “I cannot carry this for you”

Active Imagination: Dialoguing with the Foreign Feeling

Jung’s technique of Active Imagination is a powerful tool for the overwhelmed empath. Instead of being possessed by an alien emotion, they can personify it and engage it in conversation.

When I suddenly feel consumed by a grief that I have become aware is not mine, I sit in a quiet space, close my eyes, and invite an image of the Grief to appear. I then quietly witness it. It reveals itself, its nature, and ownership.

Alternatively, those not quite well established in the task of active imagination, can ask that personified image of the grief : “Who do you belong to? Why have you come to me? What do you need to show me?” These need not necessarily be verbalised questions. Mere curiosity as to the existence of the grief in your psyche can reveal the nature of grief. And though this seems like psychological gibberish, it does work because the process objectifies the emotion. It transforms the feeling from a state of being (“I am sad”) to an object of perception (“A sadness is visiting me”). The images that arise from consciouesness show you the links to your interiority.

Such cognitive restructuring creates critical psychological distance, allowing the empath to relate to the emotion instead of identifying with it, and being overwhelmed by it. The empath moves from being the actor in the drama to being the director of the play.

Creating a Symbolic Container: The Mandala of the Self

The untamed empath is a vessel without a lid. Just like everything within the vessel gets tainted, infected, or boiled over, Jung emphasized the importance of creating a container for the psyche, often symbolized by the mandala—a sacred circle representing wholeness and the Self.

At its simplest, a mandala is a geometric configuration of symbols, most often a square within a circle or a circle within a square, organized around a central point. The word itself is Sanskrit (मण्डल) for “circle“ However, mandala is far more than a simple shape. It represents the universe, a sacred space, and a microcosm of the cosmos and the mind. The sacred circle originates across cultures, being an archetypal symbol, ie, it appears independently in cultures and spiritual traditions across the globe and throughout history.

Its most famous origins arise in Hinduism and Buddhism, which Jung studied in great detail, and extensively borrowed from. In these Eastern traditions, mandalas are used as spiritual teaching tools, meditation aids, and ritual instruments. A Tibetan sand mandala, for example, is painstakingly created by monks over days as a meditation on impermanence and a visualization of a purified universe. The meditator mentally enters the mandala, moving from the outer layers of illusion and distraction toward the center, which represents enlightenment, the deity, or ultimate reality.

In Native American traditions, the”Medicine Wheel” or sacred hoop is a form of mandala representing the cosmos, the cycles of life, and the interconnectedness of all things.

In Christianity, therose windows in Gothic cathedrals (like Notre Dame) are mandalas. They use the circle, radiating from a central Christ or Virgin Mary figure, to symbolize the order of the universe, divine harmony, and the light of God illuminating the world.

Alchemical drawings often featured the squaring of the circle, a mandala-like image representing the fusion of spirit (circle) and matter (square) to create the perfected “Philosopher’s Stone” or the integrated Self.

Carl Gustav Jung encountered the mandala concept in the early 20th century while studying Eastern religious texts. He soon made a revolutionary discovery: his patients, who knew nothing of these traditions, were spontaneously drawing mandala-like images in their therapy sessions.

This led him to his crucial insight – that the mandala is an archetypal symbol of the Self—the psychic totality of an individual, which includes both the conscious and unconscious mind. For Jung, the process of “Individuation“—the lifelong journey of integrating the unconscious with the conscious to become a whole, psychologically unique individual—was often symbolized by the mandala.

Jung saw the mandala as a “personality blueprint.” Its symmetrical, centered structure represents the innate striving of the psyche for order, balance, and cohesion, especially during times of turmoil, fragmentation, or psychological distress (which he called “chaos”). This is the “container for the psyche.” When the psyche is “untamed” (like the “untamed empath”), it is chaotic, porous, and without boundaries—a “vessel without a lid.” The mandala, as a structured, bounded circle, represents the creation of that necessary container.

Thereafter,Jung began encouraging his patients to draw mandalas. He found this process to be profoundly therapeutic. The act of drawing a circle, organizing symbols within it, and finding a center provided a sense of stability and calm. It was a way for the unconscious to communicate its need for order and its movement toward integration.

The journey in a mandala –also the mirror for the journey of Individuation–is always from the periphery to the center. The periphery represents the everyday ego, with all its conflicts, personas, and distractions. The Center represents the Self—the true, integrated core of the personality, the goal of the Individuation process. Moving inward symbolizes leaving behind the fragmented parts of the personality and integrating them into a cohesive whole. Jung emphasized the importance of creating a container for the psyche, often symbolized by the mandala—a sacred circle representing wholeness and the Self.

For an empath, who naturally absorbs the emotional “chaos” of their environment, this container is not a luxury—it is a necessity for survival and sanity. The “Vessel without a Lid” is the uncontained, untamed empath—open to every energy, with no filter or boundary, leading to being “tainted, infected, or boiled over.” The Mandala as Container provides the symbolic and psychological “lid.” It represents the conscious act of creating a defined, sacred, and protected psychic space. The Circle being the boundary, says, “Here is me, and there is you. I can have compassion without absorbing your suffering.”

The Center as the core Self, is the empath’s own stable center of gravity, which they can return to when the outside world becomes overwhelming. It is the reminder of their own wholeness, separate from the emotions of others.

The symmetrical structure is the internal order that counteracts external chaos. It represents the practices (meditation, grounding, solitude, creative expression) that help the empath organize their inner world.

In essence, the mandala gives the empath a visual and psychological tool for what they must do internally, ie, establish a strong, centered Self within a protective boundary, transforming from a chaotic, overflowing vessel into a sacred, contained space.

For the modern empath, this “container” can be any consistent creative or ritual practice that helps to define and hold their identity. This could be painting, writing, gardening, yoga, or a daily meditation practice. These activities become a sacred space where the empath can pour out the chaotic psychic material they have absorbed and give it a form. The painting holds the sorrow; the poem contains the rage; the ritual grounds the anxiety. By giving the unformed feeling an image, the empath transforms it from a master into a servant—a source of insight rather than a source of torment.

Conclusion: The Goal of the Conscious Empath

If Carl Jung had actually written about empaths, he would not have told the empaths amongst us to shut down our sensitivity. To do so would be a mutilation of the soul, a rejection of a genuine and powerful connection to life. His goal would be more sophisticated, more challenging, and ultimately more freeing — not to become numb, but to become conscious.

The unconscious empath is a sponge, passively absorbing the psychic environment. We are at the mercy of the collective. We are wounded healers who cannot heal themselves.

The conscious empath, on the other hand, having walked the path of Individuation, becomes a mirror. We can reflect back the reality of another’s feeling with stunning clarity and compassion, without losing our own substance. We can identify that the other is projecting their need, their anger etc onto our bodies, our minds and our psyche, and can politely refuse to open the doors. We can hold a space for their pain without needing to own it as our own. This makes our sensitivity no longer a raw nerve, but a refined instrument of perception and relation.

This journey from sponge to mirror is not easy. It took me dozens of years of perpetual trying. Hence, it is the true Hero’s journey for the sensitive soul–the path from being a victim of one’s own nature, of the gift of empathy, to becoming a master of our own nature, wielding a deep, compassionate understanding of the human heart—starting with our own.

Empathy is a blessing. It should never be allowed to become a curse.

Like, Subscribe and leave a Reply